Steve Sailer this week wrote about American presidents and alcohol, which reminded me of this old favorite.

If Grant Had Been Drinking at Appomattox

By James Thurber

(“Scribner’s” magazine is publishing a series of three articles: “If Booth Had Missed Lincoln,” “If Lee Had Won the Battle of Gettysburg,” and “If Napoleon Had Escaped to America.” This is the fourth.)

The morning of the ninth of April, 1865, dawned beautifully. General Meade was up with the first streaks of crimson in the sky. General Hooker and General Burnside were up and had breakfasted, by a quarter after eight. The day continued beautiful. It drew on toward eleven o’clock. General Ulysses S. Grant was still not up. He was asleep in his famous old navy hammock, swung high above the floor of his headquarters’ bedroom. Headquarters was distressingly disarranged: papers were strewn on the floor; confidential notes from spies scurried here and there in the breeze from an open window; the dregs of an overturned bottle of wine flowed pinkly across an important military map.

Corporal Shultz, of the Sixty-fifth Ohio Volunteer Infantry, aide to General Grant, came into the outer room, looked around him, and sighed. He entered the bedroom and shook the General’s hammock roughly. General Ulysses S. Grant opened one eye.

“Pardon, sir,” said Corporal Shultz, “but this is the day of surrender. You ought to be up, sir.”

“Don’t swing me,” said Grant, sharply, for his aide was making the hammock sway gently. “I feel terrible,” he added, and he turned over and closed his eye again.

“General Lee will be here any minute now,” said the Corporal firmly, swinging the hammock again.

“Will you cut that out?” roared Grant. “D’ya want to make me sick, or what?” Shultz clicked his heels and saluted. “What’s he coming here for?” asked the General.

“This is the day of surrender, sir,” said Shultz. Grant grunted bitterly.

“Three hundred and fifty generals in the Northern armies,” said Grant, “and he has to come to me about this. What time is it?”

“You’re the Commander-in-Chief, that’s why,” said Corporal Shultz. “It’s eleven twenty, sir.”

“Don’t be crazy,” said Grant. “Lincoln is the Commander-in-Chief. Nobody in the history of the world ever surrendered before lunch. Doesn’t he know that an army surrenders on its stomach?” He pulled a blanket up over his head and settled himself again.

“The generals of the Confederacy will be here any minute now,” said the Corporal. “You really ought to be up, sir.”

Grant stretched his arms above his head and yawned. “All right, all right,” he said. He rose to a sitting position and stared about the room. “This place looks awful,” he growled.

“You must have had quite a time of it last night, sir,” ventured Shultz.

“Yeh,” said General Grant, looking around for his clothes. “I was wrassling some general. Some general with a beard.”

Shultz helped the commander of the Northern armies in the field to find his clothes.

“Where’s my other sock?” demanded Grant.

Shultz began to look around for it. The General walked uncertainly to a table and poured a drink from a bottle.

“I don’t think it wise to drink, sir,” said Shultz.

“Nev’ mind about me,” said Grant, helping himself to a second, “I can take it or let it alone. Didn’ ya ever hear the story about the fella went to Lincoln to complain about me drinking too much? ‘So-and-So says Grant drinks too much,’ this fella said. ‘So-and-So is a fool,’ said Lincoln. So this fella went to What’s-His-Name and told him what Lincoln said and he came roarin’ to Lincoln about it. ‘Did you tell So-and-So I was a fool?’ he said. ‘No,’ said Lincoln, ‘I thought he knew it.’” The General smiled, reminiscently, and had another drink. “That’s how I stand with Lincoln,” he said, proudly,

The soft thudding sound of horses’ hooves came through the open window. Shultz hurriedly walked over and looked out.

“Hoof steps,” said Grant, with a curious chortle.

“It is General Lee and his staff,” said Shultz.

“Show him in,” said the General, taking another drink. “And see what the boys in the back room will have.” Shultz walked smartly over to the door, opened it, saluted, and stood aside.

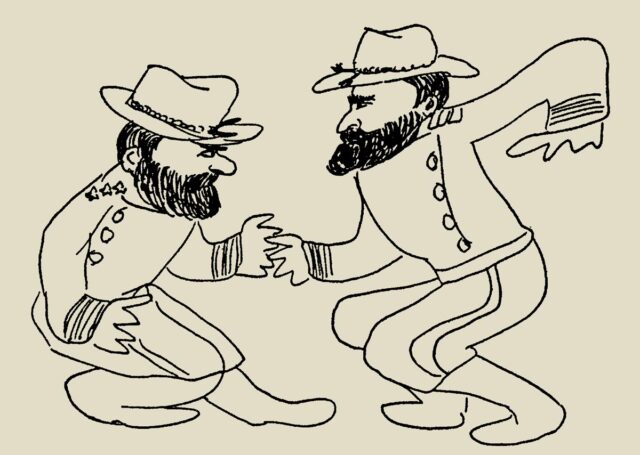

General Lee, dignified against the blue of the April sky, magnificent in his dress uniform, stood for a moment framed in the doorway. He walked in, followed by his staff. They bowed, and stood silent. General Grant stared at them. He only had one boot on and his jacket was unbuttoned.

“I know who you are,” said Grant. “You’re Robert Browning, the poet.”

“This is General Robert E. Lee,” said one of his staff, coldly.

“Oh,” said Grant. “I thought he was Robert Browning. He certainly looks like Robert Browning. There was a poet for you. Lee. Browning. Did ya ever read ‘How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix’? ‘Up Derek, to saddle, up Derek, away; up Dunder, up Blitzen, up, Prancer, up Dancer, up Bouncer, up Vixen, up -‘”.

“Shall we proceed at once to the matter in hand?” asked General Lee, his eyes disdainfully taking in the disordered room.

“Some of the boys was wrassling here last night,” explained Grant. “I threw Sherman, or some general a whole lot like Sherman. It was pretty dark.” He handed a bottle of Scotch to the commanding officer of the Southern armies, who stood holding it, in amazement and discomfiture. “Get a glass, somebody,” said Grant, looking straight at General Longstreet. “Didn’t I meet you at Cold Harbor?” he asked. General Longstreet did not answer.

“I should like to have this over with as soon as possible,” said Lee.

Grant looked vaguely at Shultz, who walked up close to him, frowning.

“The surrender, sir, the surrender,” said Corporal Shultz in a whisper.

“Oh sure, sure,” said Grant. He took another drink. “All right,” he said. “Here we go.” Slowly, sadly, he unbuckled his sword. Then he handed it to the astonished Lee. “There you are. General,” said Grant. “We dam’ near licked you. If I’d been feeling better we would of licked you.”