The typical shinigami, according to K-Ske Hasegawa in Ballad of a Shinigami: Momo, the Girl God of Death, Volume 1, atones for the crime of taking his own life by delivering death and collecting souls. He remembers only his suicide and one memory of his past life. His grim nature is reflected in his black color.

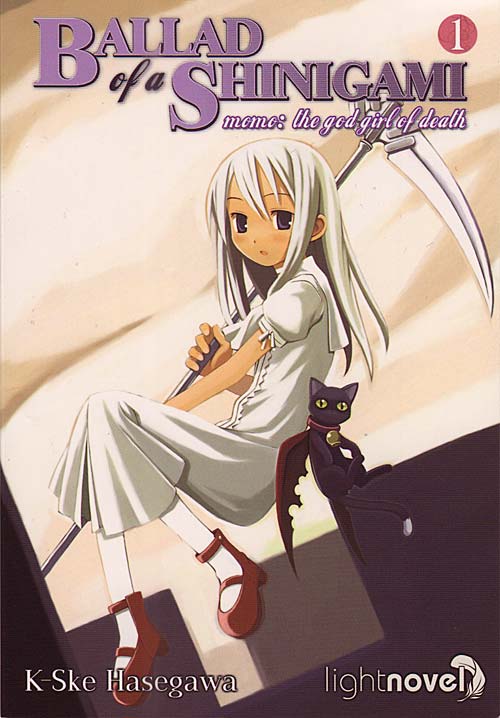

Momo, however, remembers nothing at all about her past life. She may carry a scythe, but she wears white, her hair is white and her complexion is like snow. She wears shiny red shoes. Only her eyes are dark. Unlike other shinigami, who conduct their tasks in a business-like manner, Momo takes an interest in the humans whom she encounters. This exasperates her servant demon, the winged cat Daniel.

Ballad of a Shinigami is a collection of four stories about young people who bacome acquainted with Momo. (Seven Seas labels this book a “light novel,” but it’s no more a novel than a volume of Kino no Tabi is.) Each of the first three stories is told mainly from the viewpoint of a youth who must deal with the death of someone close to him. In the first, “A Trace of Light: I Feel the Light,” a young artist considers jumping out of a ninth-floor window.

Without making a sound, Momo approached the boy. “You’re trying to kill yourself, aren’t you?” she asked.

“Er…” Daiki hesitated. And it wasn’t because his throat was dry.

“That’s odd. You do want to die, don’t you?” Momo asked. “Then why don’t you just do it?”

The boy’s body trembled upon hearing such words uttered without even a hint of emotion. Without warning, Momo giggled and moved away from him. She pointed towards the open window.

“Go ahead.”

As if hypnotized, Daiki was unable to look away from her childish yet straightforward gaze.

“If you jump from here, your wish will come true … Right? Then you’ll surely be dead.”

That word again. Death.

“Momo,” Daniel interrupted in a small, albeit urgent, tone. “Don’t you think this is wrong? He’s not on the list. If we take back an extra soul, we’ll get in trouble with the director again.”

There is indeed an aura of death around Daiki, which is why he can see the normally invisible shinigami, but it’s not his own. The story deals with his extremely strict training as an artist, his father’s relentless, crushing criticism, and their effects on Daiki’s personality and art. Through Momo’s agency, there is ultimately a reconciliation between father and son and a bittersweet ending, but, given what Daiki went through during the previous fourteen years, it’s not convincing.

The second story, “Your Voice: Echo,” will be familiar to those who watched the anime Shinigami no Ballad. A schoolboy and his friend, a sickly girl, adopt a stray kitten. Because their parents won’t allow them to keep pets, they take care of the kitten at a quiet shrine. When the inevitable happens, the boy blames the kitten for his grief. Momo and Daniel are not pleased. The third story, “The Flower of Wounds: Low Blood Pressure,” concerns another pair of students, this time the scarred children of abusive parents. In both stories, the upbeat endings seem more natural than in the first story.

The final story, “Watch the Sky: Ballad for Innocence / Momo,” is the most interesting and least satisfying tale. Unlike the other three, it is told mainly from Momo’s point of view. She and Daniel discover Towa, a little girl living in a small, square room filled with toys. Towa never leaves the room, and the only other person she has ever seen until Momo’s appearance is the man she calls “Daddy.” She looks vaguely familiar to Momo, who has no memories of a previous life. Momo and Daniel do little more than observe what happens in this story, which which ends sadly and inconclusively. I suspect that there is a continuation of Towa’s story in a further volume of Ballad of a Shinigami, perhaps revealing a connection between Towa and Momo and possibly the reason why Momo is so different from other shinigami.

Ballad of a Shinigami is illustrated by Nanakusa in a style similar to that of the anime. I don’t think Nanakusa read the descriptions carefully. Momo is repeatedly said to have skin the color of snow, but in evey color drawing she has a normal fair complexion. The blade of her scythe is supposed to be “dull-colored,” but in the pictures it’s white. There are other lapses. However, the pictures are incidental and don’t matter that much.

The book has one particular advantage over the anime adaptation: there is no mawkish soundtrack to make the reader cringe. (I dislike synth choirs in general, and at teary moments they are absolutely intolerable.)

Ballad of a Shinigami is a quick read. Although Hasegawa writes without excessive subtlety about Adolescents with Problems, she (he?) is capable of occasional humor. The book is better than the anime based on Hasegawa’s writing, and most of the stories will be new to those who have seen the series. Seven Seas rates Ballad of a Shinigami as suitable for “older teens,” but I think it’s acceptable for anyone of high school age. I can’t really recommend the book — as the excerpt above illustrates, Hasegawa is no literary artist — but, clumsy though they are, there is some substance to the stories.

This was turned into a short anime series a year or two ago.

I’ve been reluctant to pick up any of the translated light novels that have been coming out, mostly because I’m skeptical that they’ve got a good pool of translators who can handle novel-length fiction well. I just did a quick scan of Seven Seas’ forums, and their answer boiled down to “We have top men working on it right now.” “Who?” “Top. Men.”

-j

The anime is available at BOST, but only in some geographies.