Coming soon: a wacky roadtrip version of The Gulag Archipelago starring Seth Rogan and Patton Oswalt.

Category: Culture and anti-culture

But is it art?

Here Dr. Boli’s long memory gives him a different point of view from that of the average Internet blitherer. Dr. Boli’s own blithering is informed by a better acquaintance with the past two centuries or so, and in this case he remembers that we have faced exactly this question before. It took us more than a century to answer it, and it was never answered definitively. But the consensus of opinion has been that, yes, a machine can produce art, when that machine is a camera.

To anyone who has lived through both revolutions, the resemblance is hard to miss.

Previously, making a picture had been a skill learned with long and laborious practice. Then along came the machine, and the skill was irrelevant. Why learn to draw when the machine can make perfect images for you? There was much grumbling about whether such laziness ought even to be allowed, and much hand-wringing about the future of Art.

With no alteration at all, the paragraph above can be made to apply to the coming of photography in the early nineteenth century or the coming of artificial intelligence two centuries later.

Laus Deo

A portrait of a typical “rebel, monster and rule-breaker”:

There was no dazzling youthful breakthrough followed by decades of self-indulgent coasting. Haydn published his first truly revolutionary string quartets at the age of forty-two and is generally held to have written his best music in the two decades before his death at the age of seventy-seven. There was no oppressed wife patiently enabling the Great Man. (Haydn’s estranged wife derided his music and low social standing, though he supported her financially until her death.) His reputation was not the product of posthumous mythmaking. (It was fully formed within his lifetime.) Haydn upheld the social order, credited his gifts to God, and was widely described as a modest and compassionate man. He made generous provision for his servants in his will.

War, values and pianos

During the Civil War, a Union general and his troops marched into Holly Springs, Mississippi, with the intention of destroying the little Confederate town. Looking at a beautiful mansion, the general walked in, saw a fine grand in the parlor, and began playing. Upon hearing the music, a beautiful young woman descended the long staircase. After a few minutes of conversation, the pair discovered that they had both studied in New York with the same teacher. The very next day, he again came to her home and they played duets. On taking his leave he said, “You and your piano take the credit for saving Holly Springs.”

I am amused by present-day politicians who mourn the death of what they call “family values.” I would tell them to call for the return of the piano in the home. Before the endless proliferation of canned music, mothers played for family and friends a variety of music, from hymns to sentimental popular songs, while feet moved to the current dance craze, and many a romance began near a piano. There may even have been flashes of radiant beauty when mother played the first movement of the Moonlight Sonata. D. H. Lawrence describes almost unbearable nostalgia for a mother playing to her child in his magnificent poem “Piano”:

Softly in the dusk, a woman is singing to me;

Taking me back down the vista of years, till I see

A child sitting under the piano, in the boom of the tingling strings

And pressing the small, poised feet of a mother who smiles as she sings.

Today’s quote: God’s language

I’m sufficiently annoyed to facetiously propose an alternative: that a proper Christian education should be centered on abstract algebra (groups, rings, vector spaces, etc). Reasons:

- Deep exposure to math inclines students to the true philosophy: Platonism. Humanities pay too much attention to words, which inclines to nominalism.

- Ability to manipulate people (rhetoric) has greater moral hazard than ability to manipulate things.

- Unlike the classics, modern math has large contributions from Christians (Euler, Cauchy, Riemann, Cantor, etc).

- Scientists and engineers are hard-working nerds. Writers and artists are bohemian degenerates.

- Math does a better job than rhetoric or grammar in promoting clear thinking and rigorous reasoning. In math, one can’t win arguments by manipulating the meanings of words. True, classical students might study Euclid, which has the virtue of being proof-based. However, it lacks the breadth and profundity of modern mathematics, its training in abstraction, the recognition of identical structure in disparate systems, exposure to deep concepts like generators, homomorphisms, cosets, etc.

- The level of memorization required for a Latin-based education is an unnecessary barrier that math-based education evades.

- Math is God’s language.

Yeah, right

Someone at Standard EBooks is a prankster.

Memo to Arlo Guthrie

The dump still closes on Thanksgiving.

A thousand years ago, I persuaded my homeroom at high school #2 to nominate “Alice’s Restaurant” for our class song. It inevitably lost out to “The Impossible Dream,” which was the song every class picked during that historical period, but it’s pleasant to imagine my classmates sashaying into the auditorium singing “You can get anything you want / at Alice’s Restaurant, excepting Alice.”

Alice Brock, who ran the restaurant in the song (which restaurant, as Guthrie notes in the song, was not actually named “Alice’s Restaurant”) died a week ago. It sounds like she was an interesting person, though we probably would have agreed on very little.

In a Station of the Metro …

… in the twenty-first century. (Photo: Mark Fischer, from here.)

Boo, etc.

While you’re waiting for the little freaks to creep up your driveway tonight, you might enjoy viewing the work of Demizu Posuka (ポ~ン(出水ぽすか)), one of the most distinctive and prolific artists at Pixiv. Demizu reminds me of a more macabre Arthur Rackham, but he has his own peculiar style.

Today’s quote: books for children

Sometimes I answer that if I have something I want to say that is too difficult for adults to swallow, then I will write it in a book for children. This is usually good for a slightly startled laugh, but it’s perfectly true. Children still haven’t closed themselves off with fear of the unknown, fear of revolution, or the scramble for security. They are still familiar with the inborn vocabulary of myth.

Sort of a musical challenge

Show me your playlist, and I can already envision how you live.

Okay. Here is some music I recently listened to.

Now tell me how I live.

Today’s quote: the pedant as hero

The only time I have been able to impose my pedantry upon a group larger than a room of 15 or 20 students was during the time (chiefly the 1970s and ’80s) when I edited the American Scholar, the intellectual quarterly of Phi Beta Kappa. First day on the job, I outlawed from the magazine’s pages a number of words or phrases popular at the time. Among them were “input” and “feedback,” which together always sounded to me a linguistic version of peristalsis. “Charisma” was not permitted to apply to anyone of lesser stature or influence than Gandhi or Jesus. “Lifestyle” was strictly verboten, so, too, weasel words such as “arguably” or “interestingly.” “Author” used as a verb, poof!, was gone; “supportive” was never allowed in the game. “Intriguing” was permitted only if it referred to spying or diplomacy, and “impact” exclusively to car crashes and dentistry. “Caring,” “sharing,” “growing,” “parenting,” “learning experience,” and other psychobabble words were excluded.

Today’s quote: Weirdos

Great thinkers are often great weirdos; since every constellation of traits now constitutes a bona fide “identity” deserving federal protection and universal huzzahs, the weirdos ought to get into the act…. During Weirdo Appreciation Month, we’d celebrate novelist Marcell Proust (who lived in a cork-lined room), pianist Glenn Gould (who reflexively sang along to whatever Bach keyboard work he was playing), and literary Swiss Army Knife Samuel Johnson (an immense, lumbering figure who, owing to what would today be diagnosed as OCD, Tourette’s, and God knows what else, would alarm the uninitiated with his bizarre gesticulations and involuntary bird-noises). Mathematicians would be robustly represented, including Paul Erdös, who was challenged by a colleague to abstain from chemical stimulants for one month; upon successfully meeting the challenge, Erdös famously said to his colleague: “You’ve set mathematics back a month.”

Today’s quote

The American Lytton Strachey is probably H.L. Mencken his own self, and he’s a very late, very poor imitation (in that sense; I’m not sure if calling him “the American Strachey” is an insult to Mencken, or Strachey, but frankly I hope it’s an insult to both).

Today’s quote, bourgeois edition

David Stove, via William M. Briggs:

… if you write down the names of a hundred people who have done something that matters in science or literature or any other branch of culture, you will find that two at most of the hundred come from the most privileged part of the social scale, and one at most from the least privileged…

This is an extremely simple statistic, and one which is very easily verified: anyone who is prepared to take a small amount of trouble can satisfy themselves as to the fact. Yet it is of the greatest importance. If it were attended to, it would be enough on its own to silence forever revolutionary or bohemian ranting about “bourgeois culture”; for it proves that culture is everywhere, and always has been, a middle-class monopoly.

Hero vs. protagonist: the soundtrack

I’ve seen intricate taxonomies of music genres, which divide and subdivide songs into every possible category from glitch hop to folktronica. I’m told that the Spotify streaming platform has identified 1,300 different genres of music. Yet these lists never include the genre hero music—the oldest and most enduring song of them all and the root of all narratives. Like other genres, it morphs and evolves, but it never disappears.

(If you’re not reading Gioia regularly, you should be.)

Variation on a theme of G.K. Chesterton

If I only get to bring one recording to a desert island, the lyrics better be about how to make a boat.

A Great Moment ….

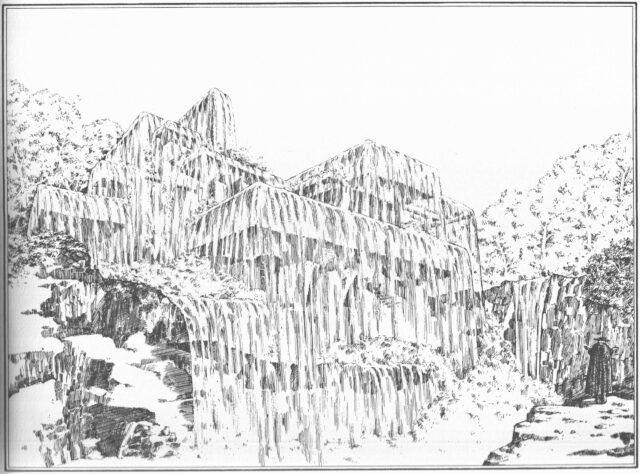

A recent discussion at Severian’s place touched on Frank Lloyd Wright, which reminded me of David Macaulay’s rendering of one of his buildings. (I used to live a few blocks from a Wright-designed house in Wichita.)

There are a few more of Macauley’s works below the fold.

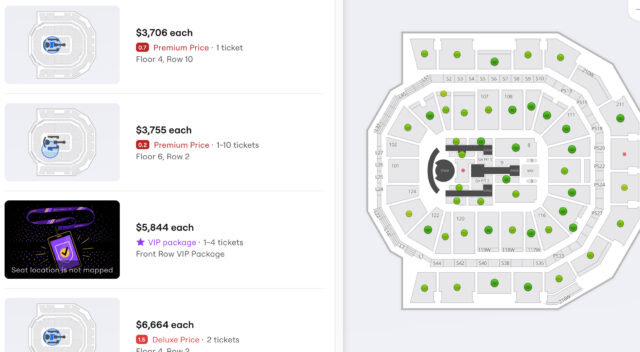

Madonn — No.

How much would you pay to watch an aging slattern perform karaoke? $666? Ten times that?

At Miss Ciccone’s performance, there will be no band, just “original multi-track recordings.”

Today’s quote

… highbrow literature fought the hero, but the hero won—albeit in the genre sections of the bookstore.

Gioia’s article, a chapter of his study of “the secret origins of musicology,” is of particular interest to those who listen to Fairport Convention, Steeleye Span and others of that ilk.