Donald Trump is no saint yet, certainly; but he has the curious quality that many saints have, of revealing serious hatred problems deep in people’s hearts, even when those people have always seemed good or normal. Some of these “good” people go stark raving mad when exposed to someone sweet, kind, and gentle, possibly because they suddenly feel inferior somehow, or feel disturbed in their view of what is possible for a human to do and be.

Trump Derangement Syndrome has a similar quality, where something innocuous or funny done by Trump suddenly works like splashing holy water on a vampire, shrieks and all. I have seen it with a member of my own family, and still don’t understand it.

Category: Decline and fall

It’s lunatic time

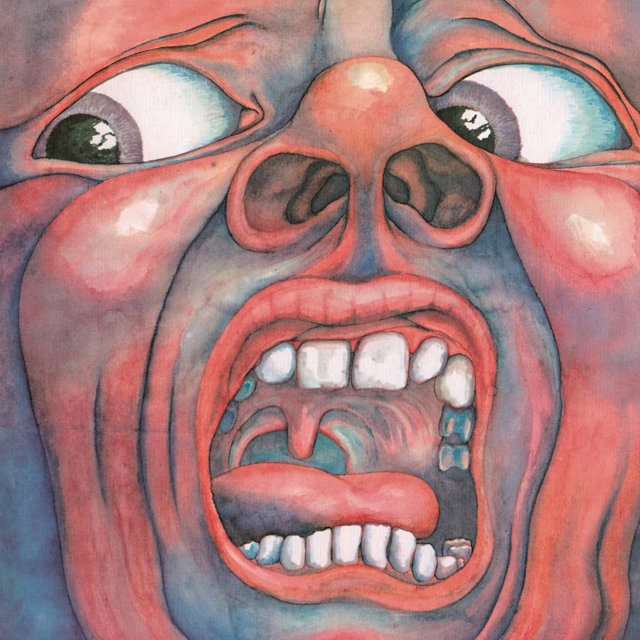

Uncle Sam was a plausible personification of the United States of America a century ago, back before the USA became Absurdistan. In this silly age of Tapioca Joe and 57 genders, he’s no longer appropriate. We need someone more in harmony with the spirit of the times. Here’s a possibility:

Clownpiece is a character from one of the later Touhou games. According to the Touhou Wiki,

With the flame of her torch, Clownpiece is able to drive others insane. According to herself, any human looking at the light of her torch would be unable to maintain their sanity, making her able to mess with their minds. In the Human Village, she used this ability to make villagers extremely irritable and short-tempered, attacking each other for trivial reasons….

The flame of the torch is able to affect the lifeforce and make it go berserk….

Clownpiece is similar in nature to many of the other fairies in Touhou: she is playful, mischievous, childish, and a little bit dumb. She enjoys the aesthetics of Hell, often leading to strange looks from others; however, this is because it reminds her of home.

Clownpiece is also the “Embodiment of impurity.”

That sounds more like 21st century America than old, irrelevant Uncle Sam.

*****

There’s another election this fall, where once again the choices will be between Very Bad or Even Worse. I suggest sending the regulatory state a message by writing in “Dave Barry.”

In his spare time, Dave is a candidate for president of the United States. If elected, his highest priority will be to seek the death penalty for whoever is responsible for making Americans install low-flow toilets.

Notes from all over

Step 1: Be me

Step 2: Notice that all the numbers in my car’s odometer display are powers of 2.

Step 3: Work out that, expressed as powers of 2, my odometer reads 31210 (82421 miles).

Step 4: Realize: “WTF–did I just differentiate my F-ing odometer??”

*****

If you’re going to give someone a Nobel Prize in economics, shouldn’t the standard be “their economic policies were put into practice in a certain community and worked as intended to the benefit of the said community”? Because otherwise, isn’t it just judging who has the most appealing theory? Which is to say, fiction being written and judged by people who don’t realize it’s fiction?

*****

I’m starting to suspect that the whole “Pride month” thing is a conspiracy by a group of rabid homophobes.

*****

In the future everyone will get canceled for fifteen minutes

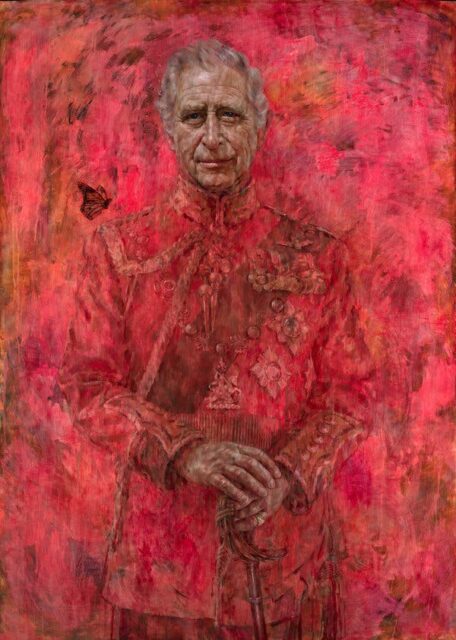

Who is more royal?

Today’s quote

“Pre-Vatican II” includes everyone from the Hildegard of Bingen to Teresa of Avila to Edith Stein. Heck, it includes most of Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton’s writings. “Pre-Vatican II” includes the life, witness and prayers of St. Francis of Assisi. “Pre-Vatican II” includes, well, every single Catholic thing that emerged before 1962, I guess.

“To Leon Trotsky, with love . . . .”

Maureen Mullarkey on Frida Kahlo:

Kahlo was a minor talent inflated into a major one by identity politics (including Mexican nationalism) and artworld access provided by marriage to Diego Rivera, the great Mexican muralist. She is the darling of women who once cried over Sylvia Plath and grew up to carry @MeToo tote bags. Her painting was a relentless obsession with herself as sign and symbol of eternal female suffering—Frida, Woman of Sorrows. Her prominence owes as much to the maudlin chauvinism of her work as on the names she slept with.

Today’s question

If a museum is to be a center of creativity, thought, and conversation, how is it different from a coffeehouse? Is it just that the coffee is worse?

Historical-botanical footnote

Joseph Moore’s most recent post mentions the Iron Chancellor. That reminded me of a bit of horticultural history.

One rose I grew many years ago was a fine white hybrid perpetual called “Frau Karl Druschki.” That’s a bad enough name, but it could have been much worse. From an online discussion:

According to a reference, for some years from 1900 there was an annual competition for the best new seedling of German origin, to be named ‘Otto von Bismarck’. The rose described here is pink, from 1908. However there is an illustration dated 1900. Was that a different rose? (Or as a passing thought, a typo?)

1900 was the year that the rose eventually named ‘Frau Karl Druschki’ was entered in the competition….… ‘Frau Karl Druschki’, at the time still unnamed, had participated in the original competition in 1900, but the judges found no rose to be good enough to be called ‘Otto von Bismarck’. So, Lambert named his rose FKD and commercialzed it and was out of the game. The original prize money of 1000 Marks was increased first to 2000, then to 3000, to no vail – nothing was good enough! Finally in 1906 Kiese’s rose made it. The irony is that FKD went on to become one of the hottest introductions of the early 20th century, while Kiese’s ‘Otto von Bismarck’ almost disappeared.

You can call the rose “Snow Queen” or “Schneekönigin” if you find “Frau Karl Druschki” too clunky.

*****

Bonus foolishness: A note from the Modern Language Association’s annual meeting:

But amid the usual carnival of perversity there was one bijou we thought might interest our readers. No, it has nothing to do with, you know, literature. The denizens of the mla and indeed of the humanities departments of most of our universities wouldn’t countenance anything so retrograde. But how’s this, a session on “Vegetal Afterlives”?

“Advancing recent work in critical plant studies”—“critical plant studies”? alas, yes—“asking how plants offer vibrant models of resistance to environmental destruction through their persistent attempts to create a Plantocene, . . . panelists focus on the theme of vegetal resistance, considering how plants can offer models of resistance for human crises like systemic racism, unnatural disasters, and climate change.”

Hero vs. protagonist: the soundtrack

I’ve seen intricate taxonomies of music genres, which divide and subdivide songs into every possible category from glitch hop to folktronica. I’m told that the Spotify streaming platform has identified 1,300 different genres of music. Yet these lists never include the genre hero music—the oldest and most enduring song of them all and the root of all narratives. Like other genres, it morphs and evolves, but it never disappears.

(If you’re not reading Gioia regularly, you should be.)

An undistinguished year

Let’s take a look back at 2023….

Nah, let’s not.

… Just a few highights, then.

Excitement

Most of the thrilling action around here this past year happened in the garden. I summarize it here.

Music

This year’s musical discovery was guitarist Takeshi Terauchi, who formed his first group 60 years ago. If Dick Dale had been Japanese, he might have sounded like Terauchi.

Dick Hyman’s 1975 recordings of Scott Joplin’s music were finally re-released in their entirety this year. Jed Distler says that they’re the best, and he may be right. Previously my preferred Joplin recordings were William Albright’s — which are good (and Albright’s own ragtime music is worth investigating) — but Hyman’s are more alive and colorful, and swing better. Hyman is a jazz pianist, and it shows, particularly in his improvisations on Joplin’s rags.

Entertainment

This fall there were two first-rate anime series broadcast simultaneously. Most years there are none. If Frieren and The Apothecary Diaries maintain quality in their continuations, they are both potential classics.

Books

Most of what I read was disappointing, and what wasn’t I haven’t finished yet. The most curious was Roger Scruton’s Fools, Frauds & Firebrands, in which Scruton summarizes, as far as it can be done, the philosophical underpinnings of radical leftism. I have a hard time with philosophy; it’s often difficult to believe that most of it isn’t ultimately just complicated word games. Scruton’s book doesn’t help. Although he writes clearly and engagingly, the people whose ideas he analyzes come across as a bunch of pompous loonies proclaiming nonsense. It’s possible that Scruton is unfair to his subjects, but other things I have read by him indicate that he is generally a reasonable, temperate man. Scruton on Slavoj Žižek:

We should not be surprised, therefore, when Žižek writes that ‘the thin difference between the Stalinist gulag and the Nazi annihilation camp was also, at that moment, the difference between civilization and barbarism.’ His only interest is in the state of mind of the perpetrators: were they moved, in however oblique a manner, by utopian enthusiasms, or were they moved, on the contrary, by some discredited attachment? If you step back from Žižek’s words, and ask yourself just where the line between civilization and barbarism lay, at the time when the rival sets of death camps were competing over their body-counts, you would surely put communist Russia and Nazi Germany on one side of the line, and a few other places, Britain and America for instance, on the other. To Žižek that would be an outrage, a betrayal, a pathetic refusal to see what is really at stake. For what matters is what people say, not what they do, and what they say is redeemed by their theories, however stupidly or carelessly pursued, and with whatever disregard for real people. We rescue the virtual from the actual through our words, and the deeds have nothing to do with it.

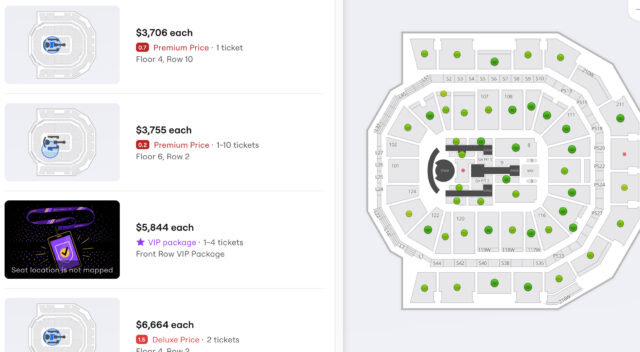

Madonn — No.

How much would you pay to watch an aging slattern perform karaoke? $666? Ten times that?

At Miss Ciccone’s performance, there will be no band, just “original multi-track recordings.”

Sanity break

Of dishwashers and cigarette lighters

The “letter to the editor” today at Dr. Boli’s magazine reminded me (and at least one other person) of Henry Kuttner’s tale from eighty years ago, “The Twonky.” I’ve occasionally wanted to post or link to the story, one of the more prophetic writings of the twentieth century, but until recently I hadn’t been able to find it online. You can read it here.1

The polls return

It’s been years since I last ran a poll. The WordPress establishment has improved its “CrowdSignal” plugin to the point of utter uselessness, so let’s see how well the free version of “Poll Maker” works.

(For context, see here. You may need to scroll down to the “nerd fight.”)

Today’s question

On what basis did we as a society decide that the ideal way to spend a childhood was to attend government institutions 5 days a week, 7 hours a day, 9 months a year, for 12 years? That most of that time should be spent sitting at a desk, with say one hour for lunch and one for recess?

(Via Isegoria.)

Joseph Moore has a notion why that happened. (Moore has quite a bit to say about modern education on his website, all of it worth reading.)