I injured my leg a couple of weeks ago, which has limited my photography. The doctor is upbeat and says I should recover fully in a few more weeks, but until then don’t expect much to look at here.

None of the current anime have held my interest. When I do feel like watching something, it’s an old show such as Shingu, where you can find the largest human yawn in Japan, above. I might give Sarazanmai another try, though probably not during my lunch hour at the office. Josh notes, among other things, that “[t]he art is often very pretty.”

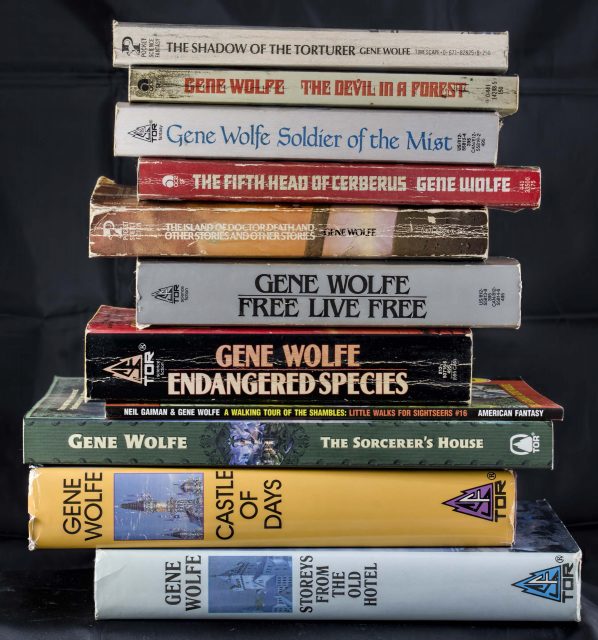

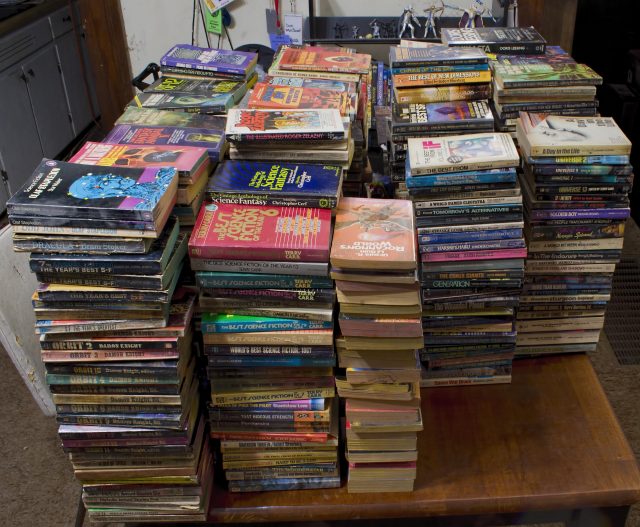

As I mentioned earlier, I finally persuaded myself to get a Kindle. I’d like to say that real, physical, print-and-paper books are clearly superior in every respect, but in fact the Kindle has one overwhelming advantage: I can make the type larger. I can read for hours now before my eyes get tired, and I’ve been taking advantage of that. Beside The Lord of the Rings, I also read Honor at Stake on Joseph Moore’s recommendation; it’s fun. I followed that with Dracula, which I hadn’t looked at since high school. Whatever your academic obsession is, you can pursue it in Stoker’s book (from Wikipedia):

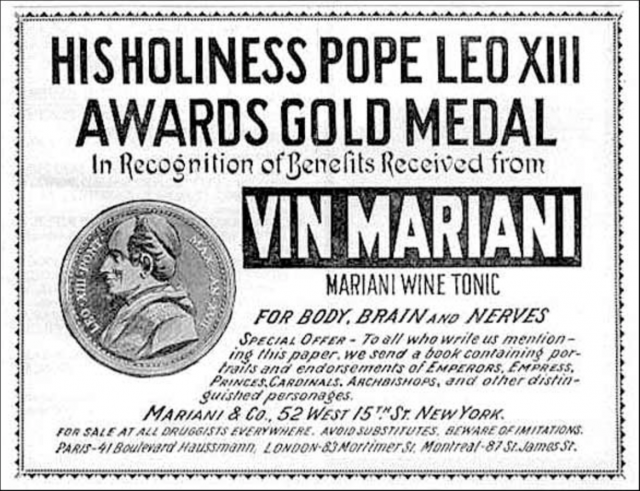

In the last several decades, literary and cultural scholars have offered diverse analyses of Stoker’s novel and the character of Count Dracula. C.F. Bentley reads Dracula as an embodiment of the Freudian id.[42] Carol A. Senf reads the novel as a response to the New Woman archetype,[43] while Christopher Craft sees Dracula as embodying latent homosexuality and sees the text as an example of a ‘characteristic, if hyperbolic instance of Victorian anxiety over the potential fluidity of gender roles’.[44] Stephen D. Arata interprets the events of the novel as anxiety over colonialism and racial mixing,[45] and Talia Schaffer construes the novel as an indictment of Oscar Wilde.[46] Franco Moretti reads Dracula as a figure of monopoly capitalism,[47] though Hollis Robbins suggests that Dracula’s inability to participate in social conventions and to forge business partnerships undermines his power.[48][49] Richard Noll reads Dracula within the context of 19th century alienism (psychiatry) and asylum medicine.[50] D. Bruno Starrs understands the novel to be a pro-Catholic pamphlet promoting proselytization.[51] Dracula is one of Five Books most recommended books with literary scholars, science writers and novelists citing it as a influential text for topics such as sex in Victorian Literature[52], best horror books[53] and criminology[54].

Considered simply as a vampire story, it’s not bad, though the plot occasionally requires that the characters act like idiots.

Other fiction re-read include The King of Elfland’s Daughter and The Time Machine, both good despite their authors’ quirks.